Goddard in the Press: Editorial Cartoons and Illustrations (1920-1925)

Please be sure to check out our digital exhibit site on Robert Goddard, made for the world's first liquid-fuel rocket launch centennial, which took place March 16, 1926.

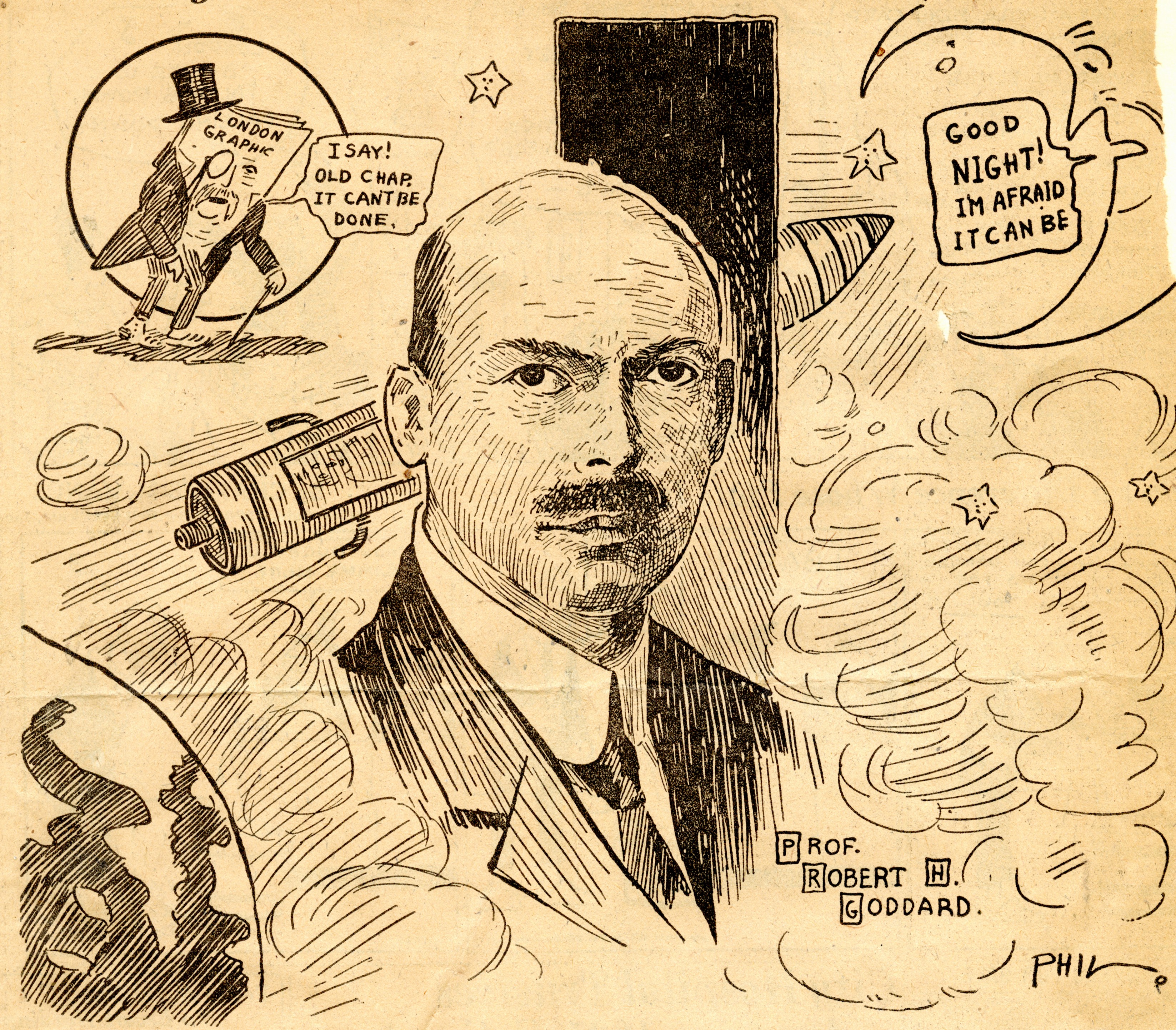

This series presents the editorial cartoons and illustrations that appeared alongside early print coverage of Robert Goddard.

From papers of record to local newspapers, the initial reportage around Goddard was largely a circus of groundless sensationalism. Collected together, this series provides insight into Goddard as a public figure and encapsulates the kinds of strategies and misinformed angles that can drive news cycles.

Ray Bradbury once wrote that “Verne is the verb that moves us to space”, which is to say that Jules Verne’s cultural and scientific influence is seismic. Robert Goddard was one of many 19th and 20th century scientists motivated by Verne, H.G. Wells, and other originators of science fiction. Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon (1865) made an enormous impression on Goddard as a child; biographer David Clary even demonstrates his proclivity for getting lost in the fantasies found in early science fiction, at times losing sight of the science required to make said fantasies reality. The very same ideas and iconography inspiring Goddard, sometimes beyond practicality, also inspired journalists to disregard fact in their reportage.

Robert Goddard’s introduction as a public figure came soon after December of 1919, when Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections published his paper “A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes”. This paper would go on to become Goddard’s most important published work, detailing years of vacuum experiments offering mathematical proof that solid-propellant rockets (he would not switch to liquid fuel until 1921) were capable of reaching beyond Earth’s atmosphere. It was the first published proof of its kind. At this time, the notion of any kind of rocket travel had no footing in reality, and rocketry’s potential was primarily positioned as a vehicle for carrying scientific instruments into outer space.

The Smithsonian then gave a press release for ‘Extreme Altitudes’ to announce Goddard’s findings. A press release for the kinds of academic and technical work published in Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections was highly unorthodox and is directly responsible for Robert Goddard becoming a public figure when he did.

Goddard only mentions the Moon near the end of his nearly eighty-page paper. In a brief piece of extraneous speculation, he considers the challenge in acquiring proof of extreme altitudes, suggesting a mass of flash powder be sent to the Moon to ignite on impact. The flash of this ‘flash powder’ scenario proved too enticing to the Smithsonian publicist, who ended the press release by stating “the possibility of sending to the surface of the dark part of the Moon a sufficient amount of the most brilliant flash powder…. its successful trial would be of great general interest as the first actual contact between one planet and another”. Journalists saw ‘rocket’ and ‘Moon’ in the press release, and the media firestorm began.

“Modern Jules Verne Invents Rocket to Reach Moon” (Boston American), “Hopes to Reach Moon With a Giant Rocket” (New York Times) and “Savant Invents Rocket Which Will Hit Moon” (San Francisco Examiner), and “Will Giant Rockets be Atlantic Liners of the Future?” (Boston Post) are some typical headlines from January 1920. Illustrations, some of which tied in other current events such as annexation projects, Babe Ruth, Jack Dempsey vs. Georges Carpentier, and the Bolsheviks, accompanied the following days, weeks, and months, and can all be seen in this series. By February of 1920, the Moon became Mars and the rocket was now carrying passengers who hustled their own news cycles by publicly volunteering. A sampling of those headlines include “Prof. Goddard Will Shoot Big Rocket Toward Mars” (Worcester Post), “Proposes Leap to Mars; New York Police Flier Would Do It with Aid of Rocket” (Boston Herald), "First Volunteer For Leap to Mars; Captain Claude Collins of Philadelphia Offers Himself to be Passenger in Rocket” (New York Times).

Goddard quickly attempted to balance the exaggerations with his own press releases (to both the general press and scientific press), making sure to bring up the necessary funding needed to make such experiments possible. These attempts only created more unintentional headlines. In his first statement to the press, he mentions “the possibility of taking photographs in space”, which became “Goddard Rockets To Take Pictures” (New York Times).

In April of 1920, the National Geographic falsely announced that Goddard was ready to test his rocket apparatus that summer, with the eventual goal of reaching the Moon. It is unknown why the National Geographic reported this. “Dr. Goddard’s Moon-Going Sky-Rocket to Be Sent Up From Worcester in July” (Worcester Telegram) and “New Rocket Will Hit the Moon” (Brooklyn Eagle), were typical of that resulting news cycle.

Coverage that wasn’t purely sensationalistic tended towards skepticism or bemusement. It was an ouroboros effect, as the skepticism was largely in reaction to the reportage, itself the result of a press release that fixated on the sole outlandish component of Goddard’s report. When The New York Herald asked how “anyone can seriously entertain even for a moment the idea that the space between two planets millions of miles apart can be traversed by the none too modern rocket”, it is hard to disagree knowing the writer is reacting to distortions. Yet, Robert Goddard, the newspapers, and the public had the same fantasy. In his attempts to set the record straight, Goddard always mentioned the Moon alongside the need for funding, knowingly pairing the two in the hopes of attracting benefactors.

News coverage of Goddard’s “Moon rocket” was worldwide, seeding Jules Verne’s visions of spaceflight into the realm of possibility for the public. The fantasy of Goddard’s ‘Moon rocket’ went on to ignite imaginations the worldwide over in the same way Verne’s fantasies had for Goddard himself. Socio-culturally, it was a major contributor to the space craze of the 1920s, particularly in the United States, Germany, and post-revolutionary Russia. Not coincidentally, Hermann Oberth and Konstantin Tsiolkovoskii, along with Goddard, make up the ‘fathers of modern rocketry’ trifecta. These countries were already taken with space exploration, but the 1920s began to fuse space travel and national identity in ways that shaped 20th century history.

Goddard received almost no press at the time of his most famous achievement, successfully launching the world’s first liquid-propellant rocket on March 16, 1926. This was because Goddard chose to not to announce this accomplishment to the press, in part due to his early

Photographs were scanned at 400dpi.

Some of these illustrations reflect the time period in which they were written, may include outdated or offensive terminology and/or caricatures.

Written by Katie Stebbins, Digital Projects Librarian

!["Science Has Actual Plans for Rocket to Sail Around the Moon", various publications [2] by Herb Roth "Science Has Actual Plans for Rocket to Sail Around the Moon", various publications [2] by Herb Roth](https://commons.clarku.edu/goddardcartoons/1045/thumbnail.jpg)